It is a season of unprecedented change for Philippine education, shaped by aggressive reform measures from within, with the full implementation of the new K to 12 system in 2016, and rapidly advancing movements from without, as the ASEAN Economic Community in 2015.

The five-year period between 2016 and 2021, often referred to as the K to 12 transition, presents significant challenges not just to the basic education sector, but causes a ripple effect on other sectors as well. It is also a once-in-a-generation window of opportunity for the reform of country’s entire education landscape.

THE VISION

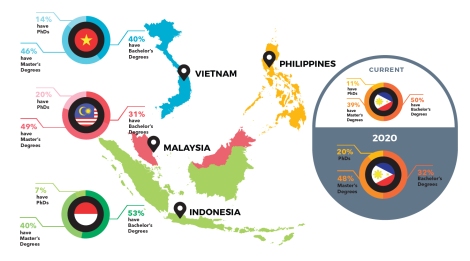

Through the development packages initiated by CHED during this period, we can envision a higher education sector able to compete with our ASEAN neighbors–where 48 percent of faculty hold master’s degrees, 20 percent have doctorates, and hundreds of degree programs all over the country meet international standards. (Read more…)

It is a large-scale investment that requires the cooperation of various government agencies, academe, and private stakeholders to ensure that the opportunity does not go to waste.

A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Education reform has been in a need in the Philippines for generations. Before K to 12, the Philippines had been one of only three remaining countries in the world–the other two being Djibouti and Angola–to have a 10-year basic education cycle. Most countries across the globe operate on a 12-year basic education cycle. (Read more…)

What was Philippine basic education like before K to 12?

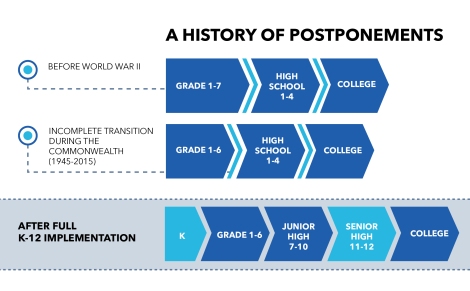

Before World War II, the Philippines had an 11-year basic education cycle: grades 1 to 7 for elementary, and 4 years of high school.

After the war, the American colonial government recommended a shift to the American system: six years (instead of seven) for elementary, three years of junior high school, and three more years of senior high school, for a total of 12 years of basic education.

The transition began with the removal of Grade 6 from elementary, but the addition of two years in high school was never completed.

Since 1945, we have made the best of ten years of basic education, the result of an incomplete transition and which was never meant to be a permanent state of affairs. Until today.

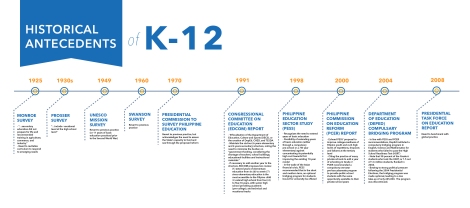

K to 12 is in fact one of the most well-studied reform measures ever to be undertaken. For decades–dating back to 1925, we’ve tried to answer two questions: (1) What should we teach in order to equip Filipinos for local needs and global standards?, and (2) How many years of school does it take to learn all these skills and information?

Historical antecedents show that it was never a question of whether we should adopt K to 12, but when it should be done.

With the current paradigm shifts in education, and with the establishment of qualifications reference frameworks regionally and globally, this long-overdue upgrade has become an imperative.

Finally, in 2010, the new administration identified education reform at the very top of its priorities, and pushed for this reform through the Enhanced Basic Education Program, or K to 12. K to 12 isn’t simply a matter of adding two more years of school; it is the product of decades of study, and a larger process of reforming the education sector as a whole. The passage of the Enhanced Basic Education Act, or Republic Act 10533 aims to ensure the continuity of the reform beyond this generation, and into the next.

THE TRANSITION IN HIGHER EDUCATION

The K to 12 system was signed into law with the passage of the Enhanced Basic Education Act of 2013 (Republic Act 10533). It clearly states that the K to 12 reform is an effort not exclusive to the Department of Education (DepEd), but cuts across the whole landscape of Philippine education and labor, making a unique impact on each sector, while at the same time requiring all these agencies to work together to ensure a smooth transition into the new system. (Read more…)

The Enhanced Basic Education Act of 2013

RA 10533 outlines the role of CHED in this reform, which is fourfold:

- Curriculum consultation (Sections 5 and 6) – CHED has been actively involved as part of the curriculum consultative committee for K to 12. CHED has tapped experts from universities to contribute to designing and revising the K to 12 curriculum.

- Teacher training and education (Section 7) – CHED is also mandated to partner with DepEd and other institutions for teacher training and education, including making sure that the curricula of teacher education institutions meet standards of quality. This ensures that the teachers of the next generation are equipped to teach young Filipinos under the new K to 12 system.

- Career guidance and counseling (Section 9) – CHED is mandated to partner with DepEd and DOLE in career guidance and counseling activities for high school students. Helping students choose what courses to take in college can help them pursue careers that lead to better jobs.

- Strategizing through the transition (Section 12) – Lastly, CHED is mandated to help formulate and implement strategies to ensure a smooth transition into the new K to 12 system. This includes making sure that the college curriculum is revised to complement the new K to 12 curriculum. CHED is also mandated to implement strategies to protect higher education institutions and their employees from severe losses during the transition.

Its Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR), promulgated in September 2013, add:

- Review SUC financing policy framework (Section 30.2) – CHED will work with the Department of Budget and Management (DBM) in reviewing the financing policy framework for state universities and colleges (SUCs) to optimize the use of government resources.

- Develop a contingency plan (Section 30.3) – CHED shall partner with DepEd, TESDA, PRC and DOLE to develop a contingency plan by School Year 2015-2016, given that the low number of graduates during the transition period will mean reduced human resources.

- To uphold educational institutions and their employees (Section 31) – CHED is mandated to ensure “the rights of labor as provided in the Constitution, the Civil Service Rules and Regulations, Labor Code of the Philippines, and existing collective agreements,” as well as “the sustainability of the private and public educational institutions, and the promotion and protection of the rights, interests and welfare of teaching and non-teaching personnel.”

Impact on the Higher Education Sector

The new K to 12 curriculum in basic education will inevitably impact higher education in the Philippines on two important fronts: the curriculum, and the people working in the higher education sector.

First, K to 12 makes it necessary to adjust the college curriculum, to make sure that college subjects build upon it in the best way.

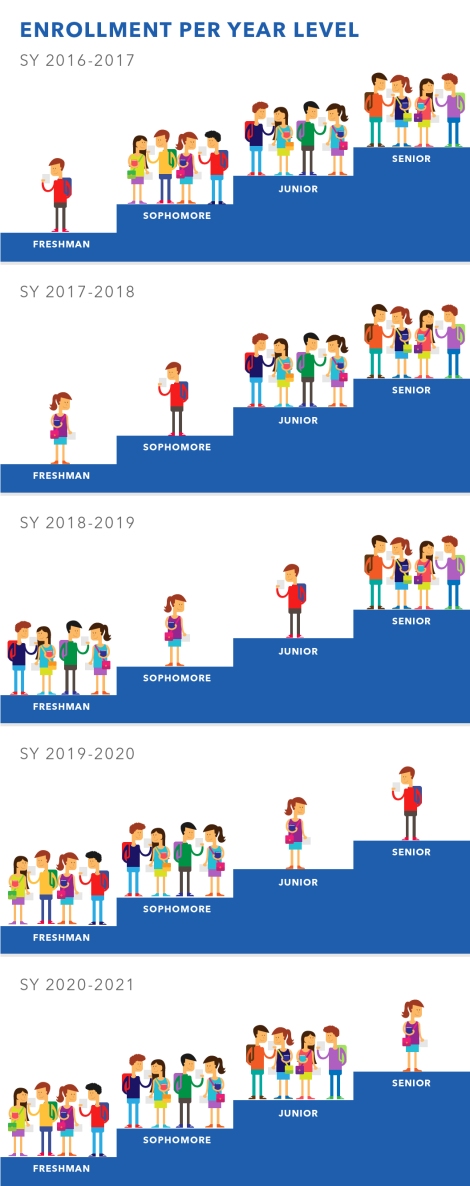

Second, K to 12 impacts those working in the higher education sector: as senior high school is rolled out nationwide this 2016, students go through two more years of high school instead of going straight to college, resulting in low enrollment in colleges and universities nationwide.

This makes the private higher education sector especially vulnerable to loss of revenue, since they depend almost entirely on tuition for salary of their personnel and operating expenses of the schools. Low enrollment means low teaching loads, and low salaries for faculty, resulting in a diminished income, or loss of jobs.

CHED has conducted studies that project the anticipated job losses during the transition period, and has partnered with DepEd and DOLE to put programs in place to ensure that personnel in the higher education sector are not only taken care of during the transition, but that this challenge is transformed into an opportunity to upgrade higher education in the country.

Impact on College Curriculum

One of the important ways that CHED has updated the curriculum before the full K to 12 implementation is by aligning it with outcomes-based education–the same pedagogy used in K to 12. CHED also came out with guidelines for the revised General Education Curriculum to complement the new subjects that will be taught in senior high.

The General Education Curriculum courses have been reduced from 64 to 36 units, composed of the following:

- Understanding the Self / Pag-Unawa sa Sarili

- Readings in Philippine History / Mga Babasahin Hinggil sa Kasaysayan ng Pilipinas

- The Contemporary World / Ang Kasalukuyang Daigdig

- Mathematics in the Modern World / Matematika sa Makabagong Daigdig

- Purposive Communication / Malayuning Komunikasyon

- Art Appreciation / Pagpapahalaga sa Sining

- Science, Technology and Society / Agham, Teknolohiya at Lipunan

- Ethics / Etika

This is in addition to nine elective units and the three-unit course on the Life and Works of Rizal.

Currently, CHED technical panels for each particular course/field are reviewing the college curriculum and fine-tuning the courses not just for GE, but for each specialization. By the time the first batch of K to 12 graduates enter college in 2018, these revisions will also be in place.

Impact on Higher Education Workers

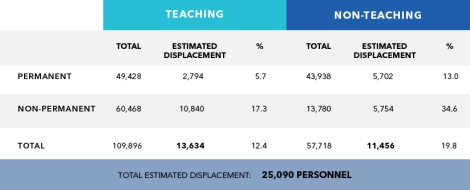

It is not true that 80,000 people stand to lose their jobs in light of the transition. The estimated displacement stands at 25,000 people.

CHED, together with the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) and the University of the Philippines Population Institute (UPPI), has come up with the following estimates on the number of people who may lose their jobs over the five-year transition (as of April 23, 2015):

Why only 25,000?

- This is based on the latest data from CHED (November 2014 survey of higher education institutions and their faculty).

- This takes into account the latest data from DepEd, namely, that 637 higher education institutions will open and operate senior high schools (as of May 31, 2015). This means they will continue to have enrollees and can keep their personnel through the transition period, and may even need to hire more teachers later on. More higher education institutions are expected to open senior high schools as 2016 draws nearer.

- These numbers do not include employees from state universities and colleges (SUCs), because the SUC budgets for the transition years are enough to cover all the people who would otherwise be displaced, nor does it include permanent workers from local universities and colleges (LUCs), because these employees cannot be retrenched during the transition period (except on grounds of incompetence or immorality).

- It was also taken into account that 25 percent of GE subjects are taught in third and fourth years–meaning not all faculty who teach GE will be displaced.

Of course, just because the numbers are not as big as what is commonly, and mistakenly, touted in the media and by anti-K to 12 groups does not mean it should be taken lightly. Those are still 25,000 jobs, and potentially 25,000 households whose livelihoods are threatened. This is precisely why CHED, DepEd and DOLE have designed responses to provide support to those who may lose their jobs:

DepEd Green Lane – The Department of Education needs to hire 30,000 new teachers and 6,000 new non-teaching staff in 2016-2017 alone, and about the same number again for 2017-2018–more than enough to absorb all the displaced personnel from the higher education sector. DepEd will open a “Green Lane” to prioritize and fast-track their hiring, in keeping with RA 10533, and will match them according to locality and salary.

DOLE Adjustment Measures Program – Those who will opt not to transfer to DepEd, on the other hand, will benefit from the Adjustment Measures Program of the Department of Labor and Employment. DOLE will provide income support for a maximum duration of one year, employment facilitation that matches their skills to the current job market, and training and livelihood programs in case they may want to pursue entrepreneurship.

CHED Development Packages

CHED, for its part, has designed the following development packages for faculty and staff who will experience a much lower workload during the transition, with the view of not only curbing the adverse effects of the transition but also, and more importantly, upgrading higher education in the country:

- Scholarships for Graduate Studies and Professional Advancement – CHED will give a total of 15,000 scholarships to higher education personnel: for 8,000 to complete master’s degrees and another 7,000 to finish doctorate degrees.

- Development Grants for Faculty and Staff – Those who may not wish to go on full-time study may still avail of grants that will allow them to retool, engage in research, community service, industry immersion, and other programs throughout the transition period.

- Innovation Grants for Institutions – Higher education institutions may likewise apply for innovation grants to fund the upgrading of their programs through: (1) international linkages, (2) linkages with industry, (3) research, or (4) the development of priority, niche, or endangered programs.

The policies determining qualifications, requirements, and modes of disbursal for the Development Packages are currently being finalized and will be posted on this website shortly.